Eschar vs. Slough: What is the Difference?

Understanding the differences between eschar and slough is essential for proper wound care and treatment. Healthcare professionals play a pivotal role in diagnosing, assessing, and implementing suitable treatments to address these types of wounds. With the right approach, including proper debridement and appropriate wound dressings, effective wound healing can be facilitated, leading to better outcomes and quality of life.

If you or someone you know has suffered a serious wound or have questions regarding the healing process, the specialized team at West Coast Wound Center can help. Book an appointment today.

Slough can be defined as “non-viable tissue of varying colour (e.g. cream, yellow, greyish or tan) that may be loose or firmly attached, slimy, stringy or fibrinous” (Haesler et al, 2022; International Wound Infection Institute [IWII], 2022). Slough consistency is determined by the tissue’s hydration status and interaction with the dressing material, as well as the depth and type of non-viable tissue (Wounds UK, 2013; Atkin, 2014).

Slough can be found in both acute wounds, such as dehisced surgical wounds, skin tears and other traumatic wounds and skin grafts, as well as in chronic wounds, such as diabetic foot ulcerse (DFUs) pressure ulcers and venous leg ulcers (Percival and Suleman, 2015).

A simple explanation of slough for patients is generally a “yellow/white layer of dead skin [tissue] in the wound, that can prevent or slow down healing” (Harding et al, 2020). Slough can be unpleasant and disturbing for the patient, and difficult to manage clinically as it prevents dressings and topical treatments from supporting the underlying viable tissues (Pritchard and Brown, 2013). Slough or necrotic tissue can promote bacterial growth and biofilm formation, inhibit the penetration of antibiotics, prevent the formation of granulation tissue, and subsequent re-epithelialisation, and interfere with wound contraction (Steed, 2004; Lewis et al, 2008; Ramundo and Gray, 2008).

The scale of the problemWhile slough is under-reported in the literature, it is known to be a feature of non-healing wounds (Pritchard and Brown, 2013). In the United Kingdom, Guest et al (2020) reported that there were an estimated 3.8 million patients with a wound managed by the NHS in 2017/18, of which 70% healed in the study year (89% and 49% of acute and chronic wounds healed, respectively); an estimated 59% of chronic wounds healed if there was no evidence of infection, compared to 45% if there was a definite or suspected infection.

In the United States, Medicare cost estimates for acute and chronic wound treatments range from $28.1 to $96.8 billion. The highest expenses are associated with surgical wounds, followed by DFUs, with a higher trend toward costs associated with outpatient wound care compared with inpatient (Sen, 2019). In Australia, DFUs approximately affect 50,000 people, costing healthcare systems an estimated $1.6 billion, and resulting in 28,000 hospital admissions and 5000 amputations each year (Chen et al, 2022). Increasing health care costs, an ageing population, recognition of difficult-to-treat infection threats, such as biofilms, and the continued threat of diabetes and obesity worldwide make chronic wounds a substantial clinical, social and economic challenge (Sen, 2019).

The impact of living with a wound carries a substantial personal cost and can have a significant effect on daily life and overall wellbeing (Moore et al, 2016). Individuals living with wounds report feeling unsupported and uninvolved in decisions about their care (Harding et al, 2020). This can lead to psychological issues, such as anxiety and depression (Wounds International, 2012).

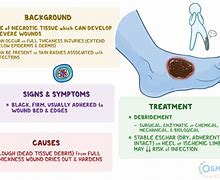

Management of slough in practiceDebridement is regarded as an essential component of wound preparation and management (IWII, 2022) and is defined as “the removal of devitalised (non-viable) tissue from or adjacent to a wound”.Debridement promotes a stimulatory environment by removing and managing exudate, while also creating a window of opportunity where biofilm defences are temporarily interrupted, allowing for increased efficacy of topical and systemic management strategies (Wolcott et al, 2010; World Union of Wound Healing Societies [WUWHS] 2019; IWII, 2022).

Debridement should not be confused with wound cleansing, which is “actively removing surface contaminants, loose debris, non-attached non-viable tissue, microorganisms or remnants of previous dressings from the wound surface and its surrounding skin” (Haesler et al, 2022).

Best Type of Wound Dressing When Dealing with Eschar

Choosing appropriate wound dressings when dealing with eschar is crucial. Dressings that maintain a moist wound environment while facilitating the removal of excess exudate are typically preferred. Wound specialists may recommend hydrogels, hydrocolloids, or specific foams depending on your circumstances to aid in its removal and promote healing.

Eschar Found in Pressure Ulcers

Eschar commonly develops in pressure ulcers, which result from prolonged pressure on the skin, limiting blood flow and causing tissue damage. Eschar in pressure ulcers can hinder healing and requires specific attention to prevent infection and support recovery.

Eschar Treatment and Wound Care

Slough: Exploring its Nature

Slough is a soft, yellow or white, stringy or thick substance, that overlays the wound bed. Composed of dead cells, fibrin, and other substances, it indicates an unclean or stagnant wound environment, hindering healing and increasing infection risks.

%PDF-1.5 %µµµµ 1 0 obj <>>> endobj 2 0 obj <> endobj 3 0 obj <>/XObject<>/Pattern<>/Font<>/ProcSet[/PDF/Text/ImageB/ImageC/ImageI] >>/MediaBox[ 0 0 720 540] /Contents 4 0 R/Group<>/Tabs/S/StructParents 0>> endobj 4 0 obj <> stream xœ�UÛnÛ0}7àà£\`ŠHݬ¡è€Þ[¬@·dèC±‡ K�‹&)ŠîëGÅNš‹í {1(™Ô9‡"EèÝÂáaïæäêÔÑŸžÀkš(PR)…Dʃ'Ö(˜ŽÓäî Ê4é]ô-36n‡óùxZÂh½[³Q¹ VÊ¡2Ñiò#Màìæ` ?‘¿Ô±*hê&¡$šÀ.ätt´¼˜iâœÛÀ·f/

How Long Can it Take For Eschar to Heal

The healing time for eschar varies based on factors such as wound size, depth, health conditions, and the body’s healing capacity. Proper management and removal of eschar play a crucial role in initiating the healing process, which can take weeks to months for complete recovery.

What is a Sloughy Wound?

Slough refers to the yellow/white material in the wound bed; it is usually wet, but can be dry, and generally has a soft texture. It can be thick and adhered to the wound bed, present as a thin coating, or patchy over the surface of the wound.

Slough consists of dead cells that accumulate in the wound exudate. During the inflammatory stage of healing, neutrophils congregate at the wound site to fight infection and clear away debris and devitalised tissue. They will often die faster than they can be removed by the macrophages and so accumulate in the wound as slough.

The presence of slough can have several different outcomes:

- Prolonging the inflammatory response

- Attracting bacteria to the wound

- Increased odour and exudate

- Preventing the wound from progressing through the wound healing process.

Pale, unhealthy granulation tissue, as noted above, can result from lack of good blood supply and angiogenesis. Pale granulation tissue needs to be freshened up with debridement to stimulate new ingrowth of blood vessels.

Pictured on the left is a necrotic sacral ulcer. The necrosis can be best visualized to the left of the wound in the photograph. Necrosis is usually dark tissue, which is completely devitalized. Necrotic tissue forms as a result of tissue death from damage. For pressure ulcers, the underlying pressure causes occlusion of blood vessels blocking vital oxygen delivery to tissues. This occlusion results in tissue death and subsequent bacterial overgrowth. In order for wounds to heal, all necrotic tissue should be debrided from the wound, a process that may take multiple attempts over months to achieve the desired outcome of good healthy granulation tissue.

The sacrococcyx ulcer demonstrates significant areas of slough. Slough is defined as yellow devitalized tissue, that can be stringy or thick and adherent on the tissue bed. This wound bed has both yellow stringy slough as well as thick adherent slough. Slough on a wound bed should be surgically debrided to allow for ingrowth of healthy granulation tissue.

Pictured left is an eschar from a pressure ulcer. Eschars result from tissue necrosis and death; they are usually black and dry. They can be firmly adherent to the wound or lifting. Eschars also result from burns; especially thermal or electric burns.

The eschar is lifting and is debrided off given the underlying infection below.

Hypergranulation or proud tissue is an overgrowth of granulation tissue above the height or border of the skin edge. It is unclear why this process actually happens in wounds. Hypergranulation tissue is usually friable and bleeds and must be dealt with. Wounds cannot heal with hypergranulation because it limits the ability for epithelial cells to migrate across the wound bed and lay down collagen and epithelium.

As shown left, application of silver nitrate to the tissue bed cauterizes the hypergranulation tissue and causes it to regress.

The picture on the left is post application of silver nitrate. Wounds may also be debrided to remove the hypergranulation tissue.

As wounds heal, epithelium forms on top of granulation tissue. In the wound pictured to the left, a large area of epithelium has formed where there was previously a large open sacral ulcer. You can also see epithelial islands being laid upon the granulation tissue. Chronic wounds should be classified as re-epithelialized not healed, when closed, as they may reopen.

The process of wound healing often involves diverse tissue formations, with eschar and slough representing crucial stages in the recovery journey. Eschar and slough are terms frequently used in the context of wound healing, representing distinct stages and compositions. Proper comprehension of these stages can play an imperative role in effective wound care and treatment.

Eschar, a hardened, dry, black or brown dead tissue, forms a scab-like covering over deep wounds, such as severe burns or ulcers. It acts as a protective barrier but can impede healing, necessitating appropriate management and removal for optimal recovery.

While both eschar and scabs are composed of dried blood and fluids, they differ significantly. Scabs, typically in minor cuts, are soft and aid in healing. In contrast, eschar forms in deeper wounds, firmly attaching to the wound bed and often requiring medical intervention from a wound care specialist for removal.